The End of the Social Graph: How the Interest Graph is Changing the Game – For Now –

When Network Effects Lose Their Armor – Part 2

A few years back, I wrote a piece called 'When Network Effects Lose Their Armor' exploring the situation when technological shifts could destroy the supposedly unbreakable network effects built by giant companies. The initial post covered the case of ride-sharing networks and how self-driving cars could render them irrelevant. In this article, we will look at the case of social media companies, how their initial defensibility built around Social Graphs is disappearing, how they are creating a new one, and how the newly built one could also vanish.

As Facebook rose to dominance, it seemed that nothing could stop them. Their growth was fueled by the increasing density of connections between people as they 'friended' and 'followed' each other in masses. It was difficult for individuals to just leave and take their network with them.

Chris Dixon famously said, ‘Come for the tool, stay for the network’

This was certainly true for many years. For a long time, their position seemed unassailable. While competitors could potentially replicate their products, their true advantage was the vast and intricate Social Graphs they had built using the data of billions of users. These graphs were like a fortress, protecting their business and providing a seemingly unbreakable defense.

When WhatsApp launched, it revolutionized software design and social networking by breaking from two established conventions. First, it eliminated the need for a username and password by using the person's mobile number as their unique identifier and SMS for authentication. Second, it streamlined the process of building social connections by leveraging the user's existing address book rather than requiring them to create connections one by one manually.

As consumption gradually moved from the web to mobile, what seemed like a convenient and benign approach had actually weakened the importance of Social Graphs of companies such as Facebook. Indeed, with this setup, the Social Graph is no longer locked into a central platform but is owned by each user and can be easily transferred to a new service by simply granting new apps access to their address book. This significantly diminished the relevance of Facebook Messenger and ultimately led to the acquisition of WhatsApp.

Still, Facebook's Social Graph kept being central for content distribution as instant messaging was not the only reason people spent time on the platform. In addition, it allowed users to see posts shared by their friends, businesses, and news sources they follow. The feature gave an excellent distribution channel to influencers and companies to build an audience they can reach directly.

From my side, I gradually came to the realization that my Facebook feed had become nothing more than a tedious, uninspiring scroll of noise. The personal updates from friends were fine, but it was full of external content, shared by my connections, that I had no interest in. So, I decided to delete the app five years ago. Moving to private WhatsApp groups with my inner circle proved to be a far superior substitute for maintaining regular contact and a much more nourishing social experience.

Nonetheless, I still needed a place to find other posts about topics I was interested in beyond private messaging groups. Twitter was the best platform for that as it had a follow model not necessarily related to my social circle. The challenge was that I had to manually build lists of people in each domain, such as technology, investment, and comedy, and keep updating them over time. Slowly, the feed became more appealing as it matched the type of articles I wanted to see.

In hindsight, that was the beginning of the rise of the Interest Graph, even though, at the time, it was still thought of as a Social Graph of people we followed. But the real breakthrough app that industrialized the Interest Graph concept was TikTok. It created an algorithmic recommendation engine that dynamically builds a holistic view of users' interests while discovering and consuming the served videos. An interest profile is gradually developed depending on how long it takes to skip and how long each video is watched, among multiple other variables. The more people use it, the better the content matches what users like to see. This process occurs pretty fast in a matter of days without manual curation. In this model, the platform determines which content is recommended, not just the people that are followed or part of the social connections. This not only leads to a superior consumption experience that gets everyone strongly hooked but also renders the Social Graph almost irrelevant.

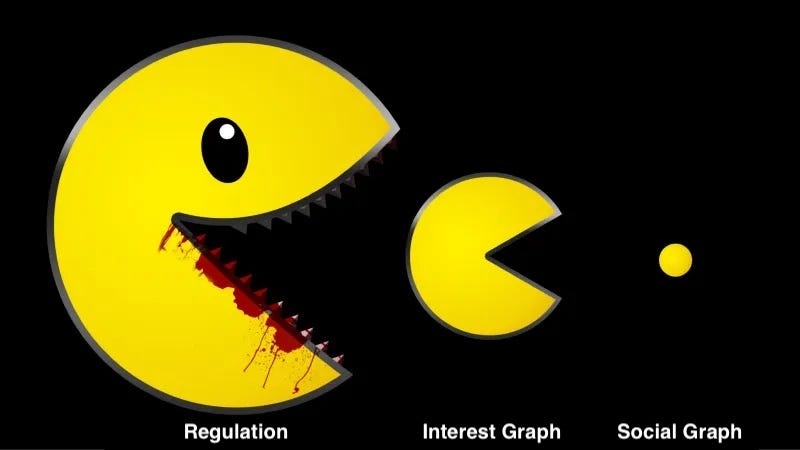

So, the defensibility of the Social Graph has been squeezed from 2 sides:

1- The shift to mobile address books for social connections and their portability across applications

2- The move to the algorithmic Interest Graph that is built independently from social connections

Consequently, Facebook had to implement a new similar interest-based model. The new algorithmic feed was done on Reels, the TikTok copycat, and the standard Instagram, which now shows many posts not originating from people you follow. On the traditional Facebook app, Meta settled for a hybrid solution. The 'home feed' is still made of content from friends, but they added a separate 'watch feed' that uses a recommendation engine to serve videos based on each user's interests.

Twitter also adopted a combined approach but implemented it within a single feed. Now, the algorithm presents a mix of tweets from both the people you follow and your interests, as determined by your past interactions and engagements. This change has dramatically improved my Twitter experience. Rather than manually searching for interesting people and checking who they follow, I now receive higher-quality posts directly in my feed. It also serves as a starting point for finding potential new accounts to follow.

It seems though that Twitter will soon follow Facebook’s approach and split into two separate feeds.

With companies utilizing recommendation engines to distribute their content, these algorithms became a powerful secret weapon unique to each platform. As the engines scale and their accuracy improves, they provide a new kind of business defensibility, replacing the lost protection of network effects based on Social Graphs.

That said, one may wonder: have the ancient social media giants really managed to adapt and evade extinction? And is the new defensibility from the proprietary Interest Graphs stronger than the former Social Graphs?

The recommendation engines based on Interest Graphs are definitely superior to the older social-based model. However, the systems used by these platforms are designed to maximize engagement rather than serve the user's best interests. They not only consider the person's interests but also act like a clever magician, using all sorts of tricks and psychological manipulations to keep people hooked, even if they are not genuinely interested in a given topic. So, while the concept is great, the current implementations and business models are problematic.

Trapped by the algorithms, people waste hours daily, consumed by a never-ending feed of videos. As a result, users suffer from various side effects, such as difficulty focusing on other tasks, anxiety, poor mental health, relationship issues, and sleep problems.

Some call TikTok 'Digital cocaine for kids'

Still, even though excessive use can poison users like a toxic substance, it doesn't hurt the platforms' defensibility. In fact, it makes them even more powerful. The more people are hooked, the more ad revenue pours in for the companies, and the more the algorithms learn about each person's preferences, the more addicted they become.

So, for now, older social media services seem to have managed to build a replacement armor made of recommendation engines, to substitute the lost protection from the Social Graph.

Yet, we have to wonder if the new reign of the Interest Graph is eternal? Or will it eventually crumble under the weight of its own power at some point?

In 2020, the US government filed an antitrust suit against Facebook, intending to break up the company due to its monopolistic practices and invasion of people's privacy.

Nevertheless, I do not believe that breaking up Meta into smaller companies would make much sense. Splitting Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram into separate legal entities would not address the underlying issues mentioned earlier. The same problems would still exist within each individual service, and the only difference would be smaller revenue for each entity. TikTok is already independent of Facebook, but it still leads to the same adverse effects.

Instead of breaking up Meta or banning TikTok, the government should release a new regulation that requires all social media providers to unbundle the content posted on their platforms from their recommendation engines. In other words, they should offer people the option to use either the built-in discovery algorithm or connect their account to an external independent engine that can prioritize their real needs and well-being.

Such a change would also require new business models to address critical questions. For instance, how the current platforms would be compensated by external engines accessing their content? And how should the independent algorithms price their service to the end user? The ecosystem will quickly fall back to the same old patterns if it's a free ad-based model. Should they be required to offer it as a paid subscription?

Once the business model questions are sorted out, implementing the proposed regulation would bring about two significant benefits. First, it would foster competition and address the government's concerns about monopolies. By requiring platforms to offer the option of using external recommendation engines, new companies could enter the market and provide alternative discovery algorithms. Second, this regulation could address issues related to manipulating user behavior and spreading misinformation. By separating content from built-in recommendation algorithms, individuals would have greater control over what they see. The reason is that independent engines would not be motivated to prioritize engagement and attention over users' well-being. As a result, users would be less vulnerable to manipulation, and the dissemination of false information would be more effectively contained.

If such regulation is adopted, social media platforms will change from puppet masters pulling the strings of user behavior and preferences through their algorithms into neutral entities for content distribution. In this scenario, the protective moat built around the Interest Graphs will disappear, leaving the platforms vulnerable and exposed to competition from newcomers.

I believe this is an inevitable scenario. It is not a matter of whether it will happen but rather when. For now, the question is, what can the current giants presently do to avoid becoming just another commodity content storage company in the future?

I really enjoyed reading this Hicham! I haven’t seen a comparable breakdown of the move to the recommendation engine and options to if not phase it out, provide a reasonable option for people to opt out. I hadn’t thought about how the move to using phone numbers to build an apps social community effected Facebook, but I can see it. Particularly now that I know so many young people are on apps like Discord. Great essay!

Thanks Michelle. Even older platforms like YouTube are a gold mine of great content that is buried under and becomes almost inexistent. I would happily pay a separate monthly subscription to have an independent recommendation engine than I can customize to show me what I want. But platforms will never open that option on their own, unless they are forced to by the government.